WHAT TO DO IF YOU NEED TO WRITE A STORY AND YOU’RE STUCK:

Mastering the art of writing captivating mysteries. Unleash your creativity and weave intricate tales of crime and suspense.

MYSTERY NOVEL BRAINSTORMING WORKSHEET

This worksheet is geared for those who want to write a mystery or crime novel. It helps with writer’s block too. It breaks down the process into small bite-sized pieces and it will get your motor going without any effort.

Just follow the suggestions, summed up easily below, and you will have at least the start of something within minutes. There is a link below to download the three-page instructional and checklist.

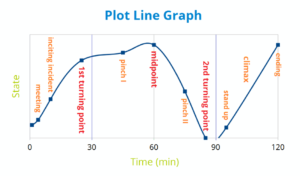

If you are an intermediate novel writer, here is a graphic of the overall process without the instructional questions:

THIS WORKSHEET HAS MULTIPLE PURPOSES:

If you are stumped for a main story, or if you are stumped for what happens now, or even if you have written yourself into a bit of a corner, this instructional will help, along with your own creativity and thinking, to bring about new possibilities.

If you are stumped for a main story, or if you are stumped for what happens now, or even if you have written yourself into a bit of a corner, this instructional will help, along with your own creativity and thinking, to bring about new possibilities.

Jump into the series of steps wherever you are in the writing process and it will help you restart your engine. Once you go through the process a time or two, I’m sure it will become your go-to procedure.

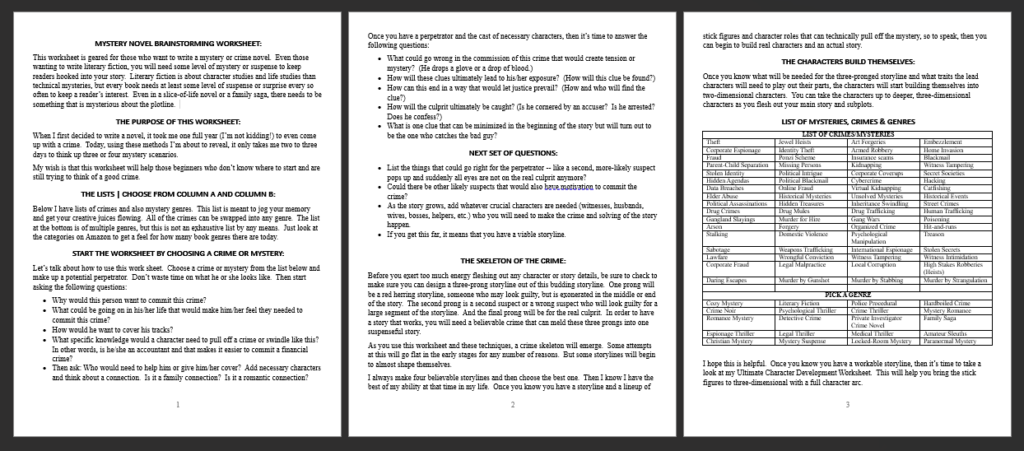

THE LISTS | CHOOSE FROM COLUMN A AND COLUMN B:

Below is a closer look at Page 3 of the Worksheet where it will give you a wide birth of choices for mysteries and/or crimes. It’s hard for one mind to think of all the possibilities without some kind of aid no matter how creative one is.

START THE WORKSHEET BY CHOOSING A CRIME OR MYSTERY:

Let’s talk about how to use this work sheet. Choose a crime or mystery from the list below and make up a potential perpetrator. Don’t waste time on what he or she looks like. Then start asking the following questions:

- Why would this person want to commit this crime?

- What could be going on in his/her life that would make him/her feel they needed to commit this crime?

- How would he want to cover his tracks?

- What specific knowledge would a character need to pull off a crime or swindle like this? In other words, is he/she an accountant and that makes it easier to commit a financial crime?

- Then ask: Who would need to help him or give him/her cover? Add necessary characters and think about a connection. Is it a family connection? Is it a romantic connection?

THE NEXT SET OF QUESTIONS TO ASK:

Once you have a perpetrator and the cast of necessary characters, then it’s time to answer the following questions:

Once you have a perpetrator and the cast of necessary characters, then it’s time to answer the following questions:

- What could go wrong in the commission of this crime that would create tension or mystery? (He drops a glove or a drop of blood.)

- How will these clues ultimately lead to his/her exposure? (How will this clue be found?)

- How can this end in a way that would let justice prevail? (How and who will find the clue?)

- How will the culprit ultimately be caught? (Is he cornered by an accuser? Is he arrested? Does he confess?)

- What is one clue that can be minimized in the beginning of the story but will turn out to be the one who catches the bad guy?

NEXT SET OF QUESTIONS:

- List the things that could go right for the perpetrator — like a second, more-likely suspect pops up and suddenly all eyes are not on the real culprit anymore?

- Could there be other likely suspects that would also have motivation to commit the crime?

- As the story grows, add whatever crucial characters are needed (witnesses, husbands, wives, bosses, helpers, etc.) who you will need to make the crime and solving of the story happen.

- If you get this far, it means that you have a viable storyline.

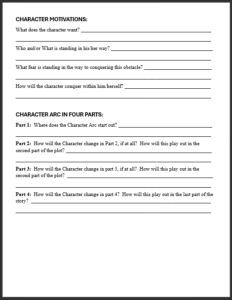

THE SKELETON OF THE CRIME:

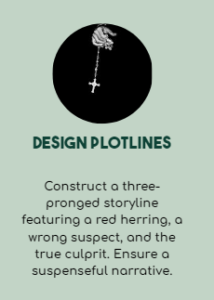

Before you exert too much energy fleshing out any character or story details, be sure to check to make sure you can design a three-prong storyline out of this budding storyline. One prong will be a red herring storyline, someone who may look guilty, but is exonerated in the middle or end of the story. The second prong is a second suspect or a wrong suspect who will look guilty for a large segment of the storyline. And the final prong will be for the real culprit. In order to have a story that works, you will need a believable crime that can meld these three prongs into one suspenseful story.

Before you exert too much energy fleshing out any character or story details, be sure to check to make sure you can design a three-prong storyline out of this budding storyline. One prong will be a red herring storyline, someone who may look guilty, but is exonerated in the middle or end of the story. The second prong is a second suspect or a wrong suspect who will look guilty for a large segment of the storyline. And the final prong will be for the real culprit. In order to have a story that works, you will need a believable crime that can meld these three prongs into one suspenseful story.

As you use this worksheet and these techniques, a crime skeleton will emerge. Some attempts at this will go flat in the early stages for any number of reasons. But some storylines will begin to almost shape themselves.

As you use this worksheet and these techniques, a crime skeleton will emerge. Some attempts at this will go flat in the early stages for any number of reasons. But some storylines will begin to almost shape themselves.

I always make four believable storylines and then choose the best one. Then I know I have the best of my ability at that time in my life. Once you know you have a storyline and a lineup of stick figures and character roles that can technically pull off the mystery, so to speak, then you can begin to build real characters and an actual story.

THE CHARACTERS BUILD THEMSELVES:

Once you know what will be needed for the three-pronged storyline and what traits the lead characters will need to play out their parts, the characters will start building themselves into two-dimensional characters. You can take the characters up to deeper, three-dimensional characters as you flesh out your main story and subplots.

LIST OF MYSTERIES, CRIMES & GENRES

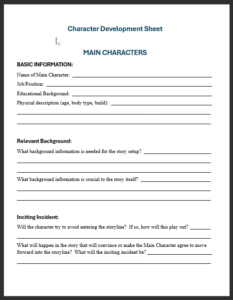

I hope this is helpful. Once you know you have a workable storyline, then it’s time to take a look at my Ultimate Character Development Worksheet. This will help you bring the stick figures to three-dimensional with a full character arc.

Writing a novel is a huge undertaking. There are many things that go into the writing of a fiction story. The best tip I can pass on is this: Break everything down into little bite-sized pieces. By doing this, you can reduce a huge project down to do-able portions that can be done whether you have 2 hours a week to write or two full days! It only requires a little planning and organization.

Writing a novel is a huge undertaking. There are many things that go into the writing of a fiction story. The best tip I can pass on is this: Break everything down into little bite-sized pieces. By doing this, you can reduce a huge project down to do-able portions that can be done whether you have 2 hours a week to write or two full days! It only requires a little planning and organization. It’s important to keep reading as your own journey as a writer continues. Each author has a different style and uses different storytelling techniques. The stories don’t even have to be great. You can learn from the good, the bad and the bland. Just analyzing what made a book bland is a great lesson in itself. Did the story need more action? Did the story get stuck somewhere?

It’s important to keep reading as your own journey as a writer continues. Each author has a different style and uses different storytelling techniques. The stories don’t even have to be great. You can learn from the good, the bad and the bland. Just analyzing what made a book bland is a great lesson in itself. Did the story need more action? Did the story get stuck somewhere?  or other books you read. Reading other authors is crucial no matter where you are on the writing spectrum. However, when you’re new, you can learn a lot from watching mystery or crime noir movies. I like movies from the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. The movies in these decades didn’t have CGI and the directors had to use the stage to tell the story. They used wider shots and props to assist the storytelling. By watching these older movies, you can learn a lot regarding writing.

or other books you read. Reading other authors is crucial no matter where you are on the writing spectrum. However, when you’re new, you can learn a lot from watching mystery or crime noir movies. I like movies from the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. The movies in these decades didn’t have CGI and the directors had to use the stage to tell the story. They used wider shots and props to assist the storytelling. By watching these older movies, you can learn a lot regarding writing.  It’s a good idea to read the synopsis before you view the movie. Knowing at least a basic outline of the story will allow you to absorb more as an author. If you go into the movie blindly, you will be “experiencing the movie” as a viewer only. By knowing ahead of time what story will be unfolding, it will allow you to watch specifically for certain scenes to unfold. You can watch what tools are used to move the story along.

It’s a good idea to read the synopsis before you view the movie. Knowing at least a basic outline of the story will allow you to absorb more as an author. If you go into the movie blindly, you will be “experiencing the movie” as a viewer only. By knowing ahead of time what story will be unfolding, it will allow you to watch specifically for certain scenes to unfold. You can watch what tools are used to move the story along.

If you are looking for a suggestion, I would suggest Rebecca for the first movie. This movie was directed by Alfred Hitchcock and it has a lot of gothic atmosphere. There is also a psychological plotline in this story so it is a goldmine for learning storytelling tools.

If you are looking for a suggestion, I would suggest Rebecca for the first movie. This movie was directed by Alfred Hitchcock and it has a lot of gothic atmosphere. There is also a psychological plotline in this story so it is a goldmine for learning storytelling tools.  When I first decided to write a novel, it took me one full year (I’m not kidding!) to even come up with a crime. Today, using these methods I’m about to reveal, it only takes me two to three days to think up three or four mystery scenarios.

When I first decided to write a novel, it took me one full year (I’m not kidding!) to even come up with a crime. Today, using these methods I’m about to reveal, it only takes me two to three days to think up three or four mystery scenarios. Let’s talk about how to use this work sheet. Choose a crime or mystery from the list below and make up a potential perpetrator. Don’t waste time on what he or she looks like. Then start asking the following questions:

Let’s talk about how to use this work sheet. Choose a crime or mystery from the list below and make up a potential perpetrator. Don’t waste time on what he or she looks like. Then start asking the following questions: Once you have a perpetrator and the cast of necessary characters, then it’s time to answer the following questions:

Once you have a perpetrator and the cast of necessary characters, then it’s time to answer the following questions:

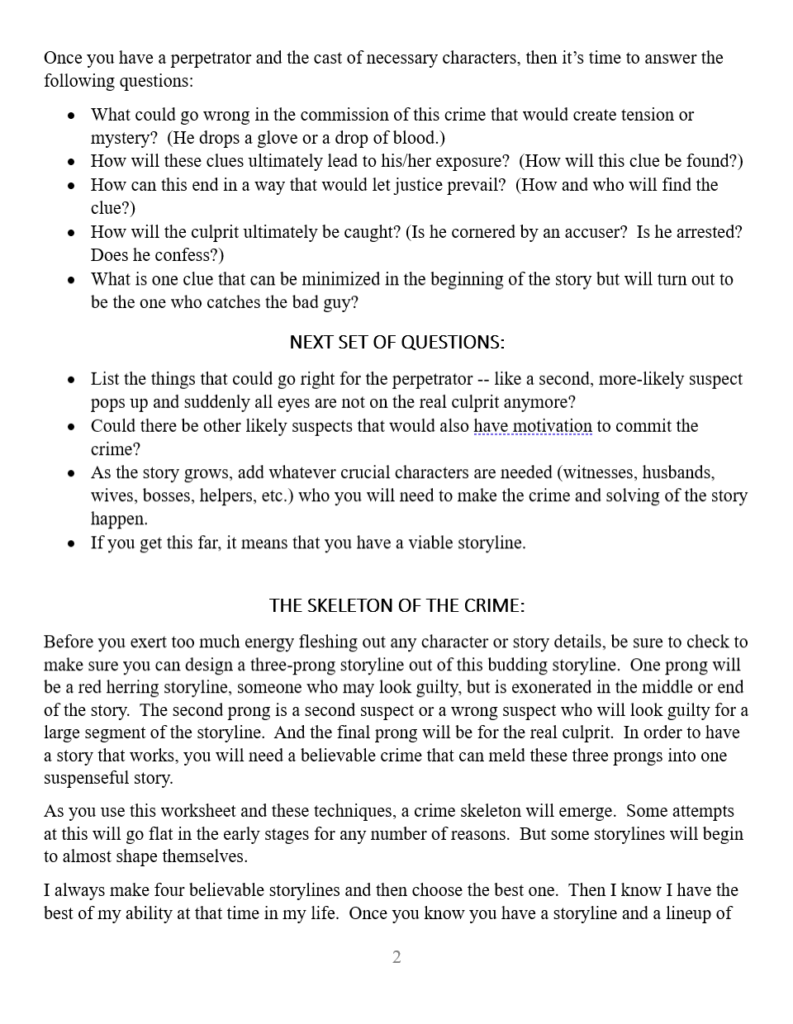

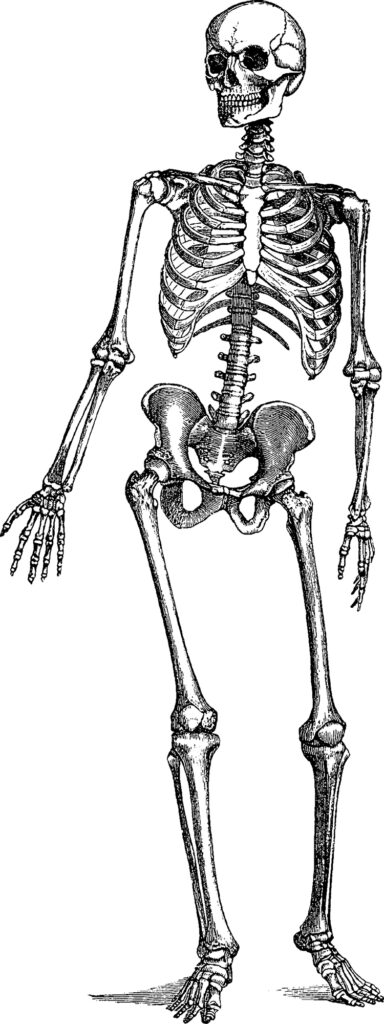

When I started writing several years ago, I came across the standard character worksheet and it focused mostly on physical attributes, occupation but there was a disconnect regarding their role in the storyline, which is the most important part.

When I started writing several years ago, I came across the standard character worksheet and it focused mostly on physical attributes, occupation but there was a disconnect regarding their role in the storyline, which is the most important part. As a newbie, it took me awhile to remember that a character needs to have an arc over the storyline. So it’s important — and time saving — to know what that arc will be before you even begin the draft. This character sheet can help you find this so you know where you are starting from and where you want to end up. The following questions should help you focus on what this character arc will be:

As a newbie, it took me awhile to remember that a character needs to have an arc over the storyline. So it’s important — and time saving — to know what that arc will be before you even begin the draft. This character sheet can help you find this so you know where you are starting from and where you want to end up. The following questions should help you focus on what this character arc will be: For minor characters, you only need to answer a few questions. It helps to know what role these minor characters will play and what, if any, background information is needed to support them in the storyline:

For minor characters, you only need to answer a few questions. It helps to know what role these minor characters will play and what, if any, background information is needed to support them in the storyline: For anyone who is new here, I use a Four Act Structure as opposed to the more-popular three-act structure. I find that middle section in the three-act structure too confusing. Over the writing of 12 novels, I gravitated to a four-part structure as it is more symmetrical and makes more sense to me. I also believe, for whatever it’s worth to anyone, that this three-act structure is responsible for the ‘lagging’ that often occurs in the middle of a story.

For anyone who is new here, I use a Four Act Structure as opposed to the more-popular three-act structure. I find that middle section in the three-act structure too confusing. Over the writing of 12 novels, I gravitated to a four-part structure as it is more symmetrical and makes more sense to me. I also believe, for whatever it’s worth to anyone, that this three-act structure is responsible for the ‘lagging’ that often occurs in the middle of a story. The inciting incident. In a murder, crime or police procedural story, this will be the crime itself and how the detectives show up in it. When the detectives are pushed into going on a quest to solve it, that’s the inciting incident. This begins the journey of the story.

The inciting incident. In a murder, crime or police procedural story, this will be the crime itself and how the detectives show up in it. When the detectives are pushed into going on a quest to solve it, that’s the inciting incident. This begins the journey of the story. Part Two is where I introduce all the suspects and their possible motivations — as the detectives are quite often guessing at this early stage of an investigation. The motivation of each of the suspects will be uncovered in some way later in Part two or even in Part 3.

Part Two is where I introduce all the suspects and their possible motivations — as the detectives are quite often guessing at this early stage of an investigation. The motivation of each of the suspects will be uncovered in some way later in Part two or even in Part 3. The end of Part Two usually marks the midpoint of the book. I like to end this section with a .big reveal of some kind. Or maybe a clue that turns the investigation into another direction. There could even be a new murder, or the surfacing of an unusual suspect, or someone gets caught in a big lie that changes the direction of the investigation.

The end of Part Two usually marks the midpoint of the book. I like to end this section with a .big reveal of some kind. Or maybe a clue that turns the investigation into another direction. There could even be a new murder, or the surfacing of an unusual suspect, or someone gets caught in a big lie that changes the direction of the investigation. Now the investigation gets a little stressful. The detectives may not agree on who the guilty party is, or maybe they know who it is but can’t find the legal evidence to prove it. Maybe they are operating only on gut feeling and speculation at this point. They are rushing against the clock or against other forces working against them to solve it, catch the guilty party or find compelling and irrefutable evidence.

Now the investigation gets a little stressful. The detectives may not agree on who the guilty party is, or maybe they know who it is but can’t find the legal evidence to prove it. Maybe they are operating only on gut feeling and speculation at this point. They are rushing against the clock or against other forces working against them to solve it, catch the guilty party or find compelling and irrefutable evidence. Part four is broken down into two parts. In the first half of Section 4, the crime or mystery is solved. There will be whatever drama you want to add about the solving of this crime. Whether your detectives are battling physically with someone, bullets are being fired back and forth, or entrapping the guilty party, or just uncovering that last piece of evidence that will legally prove guilt, this is where this is revealed.

Part four is broken down into two parts. In the first half of Section 4, the crime or mystery is solved. There will be whatever drama you want to add about the solving of this crime. Whether your detectives are battling physically with someone, bullets are being fired back and forth, or entrapping the guilty party, or just uncovering that last piece of evidence that will legally prove guilt, this is where this is revealed. The second half of Part 4 is the ‘wrap up’. This is where you will show the new normal, everyone’s life ‘in resolution’. This is where you will also explain the full growth of your characters. Many author’s don’t do this, but I don’t like to read books where things end where the reader is left to decide what it all means. I may have my own opinions, but I like to know what the author meant by the story. So I make sure I explain, again very quickly, how things are ending in a narrator voice.

The second half of Part 4 is the ‘wrap up’. This is where you will show the new normal, everyone’s life ‘in resolution’. This is where you will also explain the full growth of your characters. Many author’s don’t do this, but I don’t like to read books where things end where the reader is left to decide what it all means. I may have my own opinions, but I like to know what the author meant by the story. So I make sure I explain, again very quickly, how things are ending in a narrator voice. Most new writers want to get to the writing already. But in this layer of writing, all plot holes or inconsistencies will show up. Any clues that won’t work when adding more suspects and motivations will show up in this layer.

Most new writers want to get to the writing already. But in this layer of writing, all plot holes or inconsistencies will show up. Any clues that won’t work when adding more suspects and motivations will show up in this layer. My template is short but it keeps me on track. I’ll break it down below. This small template I use keeps my writing on point and tight. It prevents me from meandering, dawdling, going off on an irrelevant tangent or writing myself into a corner.

My template is short but it keeps me on track. I’ll break it down below. This small template I use keeps my writing on point and tight. It prevents me from meandering, dawdling, going off on an irrelevant tangent or writing myself into a corner. n order to prevent head-hopping, which is very common among new writers, you need to be constantly reminded that each scene is in one perspective. Some writers write in first person and that’s easy.

n order to prevent head-hopping, which is very common among new writers, you need to be constantly reminded that each scene is in one perspective. Some writers write in first person and that’s easy. I don’t know whether I am an author who is obsessed with time, or whether I use time as an element to put pressure to solve on my characters, but I have always tracked time. I find this helps me balance the story and make the story more realistic.

I don’t know whether I am an author who is obsessed with time, or whether I use time as an element to put pressure to solve on my characters, but I have always tracked time. I find this helps me balance the story and make the story more realistic. Location is important for two reasons. One reason is casts the scene in cement. You have chosen a stage for the scene to take place. I don’t write any scene or location descriptions in this layer of writing. But I can write the action of the scene in context of a location.

Location is important for two reasons. One reason is casts the scene in cement. You have chosen a stage for the scene to take place. I don’t write any scene or location descriptions in this layer of writing. But I can write the action of the scene in context of a location.

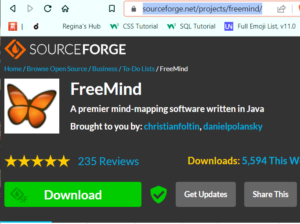

This is the second step in writing a new fiction novel. In the first step, I start out with writing four potential storylines in FreeMind, which is a mind mapping software.

This is the second step in writing a new fiction novel. In the first step, I start out with writing four potential storylines in FreeMind, which is a mind mapping software.  Most new writers want to start writing scenes and dialogue. They want to just get on with it. But the dark side of working this way is that when you find out your clues won’t work when you need to add a new suspect, you will have written two chapters already. My process will save you from writing for the trashcan.

Most new writers want to start writing scenes and dialogue. They want to just get on with it. But the dark side of working this way is that when you find out your clues won’t work when you need to add a new suspect, you will have written two chapters already. My process will save you from writing for the trashcan. Each new book requires a new plotline. I used to come up with a plotline and go with it. But I noticed I had a lot of insecurities as to whether it was good enough or whether I was choosing a plotline too soon.

Each new book requires a new plotline. I used to come up with a plotline and go with it. But I noticed I had a lot of insecurities as to whether it was good enough or whether I was choosing a plotline too soon. So I could tell the four plotlines was a working strategy going forward. The first time I did this, I opened a new Notepad document, plotted a crime and a potential storyline. When I finished, I named it the first potential plotline and filed it. Rinse and repeat. Sounds pretty straight forward, right?

So I could tell the four plotlines was a working strategy going forward. The first time I did this, I opened a new Notepad document, plotted a crime and a potential storyline. When I finished, I named it the first potential plotline and filed it. Rinse and repeat. Sounds pretty straight forward, right? Then in response to getting scattered, I just wrote all four plotlines in one document, but then I was overwhelmed by how long the document was and it wasn’t easy to see which plotline I was in. The Notepad has a tendency to return to the top when you flip out of it to check a spelling or anything. Ugh, I again went upside down.

Then in response to getting scattered, I just wrote all four plotlines in one document, but then I was overwhelmed by how long the document was and it wasn’t easy to see which plotline I was in. The Notepad has a tendency to return to the top when you flip out of it to check a spelling or anything. Ugh, I again went upside down. I spent a lot of time in researching novel templates and wound up getting more confused than organized. I may have a mental block on this, or if you are a beginner, you may find the same difficulties in getting your plot or story line to fit exactly over a template outline.

I spent a lot of time in researching novel templates and wound up getting more confused than organized. I may have a mental block on this, or if you are a beginner, you may find the same difficulties in getting your plot or story line to fit exactly over a template outline. When I began to hear terms like “panters and/or plotter” I didn’t even know what they were talking about. A pantser, if you don’t know if someone who just sits down and begins to write “by the seat of their pants” without any organization and without any plot line. They approach the writing from a completely creative process. I imagine that “natural writers” would take this approach. Maybe people who like chaos would take this route. But I would wind up staring at a blank page all day if I didn’t have at least an outline.

When I began to hear terms like “panters and/or plotter” I didn’t even know what they were talking about. A pantser, if you don’t know if someone who just sits down and begins to write “by the seat of their pants” without any organization and without any plot line. They approach the writing from a completely creative process. I imagine that “natural writers” would take this approach. Maybe people who like chaos would take this route. But I would wind up staring at a blank page all day if I didn’t have at least an outline. It is best as a beginner to choose a location and setting that you are familiar with. It will cut down on the research you need to do, as you will need to do at least some forensic and police procedure research. For example: I used to be a court reporter for 11 years and I have experience working on criminal cases, how prisoners are moved around the courthouse, how sheriff’s officers and prison guards are different from cops, what goes on in a Judge’s chambers on breaks and after the jury goes home. So this is a good setting for me to write about.

It is best as a beginner to choose a location and setting that you are familiar with. It will cut down on the research you need to do, as you will need to do at least some forensic and police procedure research. For example: I used to be a court reporter for 11 years and I have experience working on criminal cases, how prisoners are moved around the courthouse, how sheriff’s officers and prison guards are different from cops, what goes on in a Judge’s chambers on breaks and after the jury goes home. So this is a good setting for me to write about. One of the biggest mistakes I made in the beginning was focusing too much on the main character. With a mystery, you need to have a unique crime that hasn’t been done before. Because there are millions of mystery books, your specific crime may have been done, but you want to make sure you don’t pick on that has been “done to death”.

One of the biggest mistakes I made in the beginning was focusing too much on the main character. With a mystery, you need to have a unique crime that hasn’t been done before. Because there are millions of mystery books, your specific crime may have been done, but you want to make sure you don’t pick on that has been “done to death”.