Brainstorming a Storyline - Part 2

Where Do We Begin?

In the last blog entry and video, I covered a list of six initial questions that should be asked in order to raise up an initial storyline. In my experience, within a story with multiple suspects or a mystery that needs to slowly unravel, the suspects, motivations and clues need to connect first to create what I call a crime spine or a mystery spine.

Once you have all of these story parts connected, this is the easiest time to take the characters from stick figures into two-dimensional characters. The characters will be transformed into their final three-dimensional states during the actual book-writing process, so the goal in this brainstorming process is to sculpt two-dimensional characters.

Once you have all of these story parts connected, this is the easiest time to take the characters from stick figures into two-dimensional characters. The characters will be transformed into their final three-dimensional states during the actual book-writing process, so the goal in this brainstorming process is to sculpt two-dimensional characters.

So the next set of questions is designed to take your story idea from this crime/mystery spine to a second dimensional level. This is the point where you can add realistic character traits and motivations that will fit inside the plotline. I assure you, there won't be any more trying to fit a fully-fleshed out round character into a square plotline. This process will avoid that.

So the next set of questions is designed to take your story idea from this crime/mystery spine to a second dimensional level. This is the point where you can add realistic character traits and motivations that will fit inside the plotline. I assure you, there won't be any more trying to fit a fully-fleshed out round character into a square plotline. This process will avoid that.

So let's get into the second set of questions which cover the main characters, the suspects, the antagonist, and the motivations.

THE SUSPECT LIST - WHO ARE THE SUSPECTS AND/OR THE ANTAGONIST?

In a crime or murder mystery, pick two to four suspects and assign them each a motivation. If you are writing a different type of story, you will need at least one antagonist. Name the antagonist and/or suspects and choose their motivation. Do this for each suspect or antagonist.

Here is an example: A man is murdered in his house during a birthday party and there are four people at the party, all of whom can be a suspect: One of the guests is the man's child who is at odds with the father for some reason, and the child has recently been threatened with being cut out of his/her inheritance. The second suspect is the long-suffering wife who has just found out her husband is cheating again, after promising never to be unfaithful again. The third suspect could be the mistress who is not happy that her lover now wants to save his marriage and has ended their affair and cut off her mistress pay. And of course, there could be an old college buddy who is in attendance at the party, looking all innocent, but inside he is being eaten alive by a desire for revenge because of something that happened in their past. Knowing all of these characters and their motivations ahead of time will make sculpting the main character, the detective or amateur sleuth, much easier.

When I was new and watching writing video after writing video, the advice was the opposite. It was suggested over and over again to start by fleshing out a main character and plotting a story around him or her. What I found was that a fully-fleshed out character is not very flexible. You can't place a fully-fleshed out character into any storyline. For example, a quirky detective like Monk would be out of place playing James Bond. He would also not fit into any gothic story about family secrets. Nor would James Bond fit into a small-town mystery novel. A Columbo character would be out of place in a James Bond script as well. I'm sure you get the point.

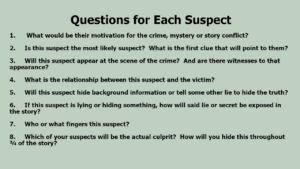

QUESTIONS FOR ANTAGONISTS OR SUSPECTS:

Go down the list or diagram of all the suspects you have chosen in your story. Ask yourself the following questions about each suspect. These questions also work in a story with only an antagonist.

- What would be their motivation for the crime, mystery or story conflict be?

- Is this suspect the most likely suspect? What is the first clue that will point to them?

- Will this suspect appear at the scene of the crime? And are there witnesses to that appearance?

- What is the relationship between this suspect and the victim?

- Will this suspect hide background information or tell some other lie to hide the truth and for what reason?

- If this suspect is lying or hiding something, how will said lie or secret be exposed in the story?

- Who or what fingers this suspect?

- Which of your suspects will be the actual culprit? How will you hide this throughout ¾ of the story?

Once you have answered each of these questions about each suspect or antagonist, you will have enough clay to now sculpt an interesting and riveting main character and storyline.

SEVENTH QUESTION: The Protagonist

Unless you are writing in a series where the main character is already fully developed, it's best to wait until after choosing the antagonist, suspects, and motivations for each of them to infuse the main protagonist with human traits. Why? Because the protagonist will need to have a character arc and this will need to be developed over the action of the story and in relation to all of the different suspects.

Unless you are writing in a series where the main character is already fully developed, it's best to wait until after choosing the antagonist, suspects, and motivations for each of them to infuse the main protagonist with human traits. Why? Because the protagonist will need to have a character arc and this will need to be developed over the action of the story and in relation to all of the different suspects.

The action of the story will be triggered by the victim, what happened, what the investigation needs to solve the mystery or crime, and the main character will need certain skills and traits to make all of this happen.

For example: If you come up with a business entrepreneur as a main character first, and give him a family, a certain job, etc., how will he have the skill set to uncover all the clues that are already in the plotline? It's easiest to look at the completed crime spine and realize that you will need a bold computer wizard who is motivated by justice more than a lucky or wealthy businessman.

Once you know who, what, when, where and how the story will proceed, now you can choose the type of protagonist needed to solve the mysteries. Now it is time to sketch in more character traits and details. This process will take your stick figure and raise it to a level of a two-dimensional character.

Once you know who, what, when, where and how the story will proceed, now you can choose the type of protagonist needed to solve the mysteries. Now it is time to sketch in more character traits and details. This process will take your stick figure and raise it to a level of a two-dimensional character.

The Protagonist List of Questions:

There are many questions to ask about the protagonist, aka the hero or good guy in the story. Below I have posted many of them to get your creative mind going.

Why is the protagonist in a position to solve the mystery? Who brings them into the story? Are they a professional detective and just get hired? If he or she is an amateur sleuth, what circumstance leads them into the scene of the crime or mystery? If it's a psychological story, how do they find themselves inside this psychological drama in the first place? Who and/or why are they now staying in a scary house or on an estate with age old secrets?

Here is a tip for Newbie writers: There are hundreds of videos suggesting you start with the main character, and this does work in very simple storylines or in simple romance stories. It doe work. But once the plotline has any number of antagonists or suspects, and there will need to be some kind of search or investigation, revealing one clue after another, it's best to know what particular steps the main character will need to go through before you breathe life into him.

In other words, if online research is needed, your MC has to have technical skills or an assistant who does. If the MC will be examining documents in old archives, he needs to have some expertise in this field and that will need to be part of his character back story. If he will be running around and jumping from one building to another or hanging off helicopters like Tom Cruise likes to do, he will need a back story about why he is in that kind of shape.

Newbie writers often get attached to characters they dream up out of thin air and then run into big problems trying to build a working story around this fully-fleshed out character. This can cause a bigger problem. It can lead to a bad case of writer's block, even a fatal case of writer's block. If you find this describes you, set aside that darling character you love and begin to brainstorm following these chronological suggestions and you may find yourself developing an equally riveting character that, with a different job or a tweaked backstory, can make a great storyline work. Remember: If you created one character that you love, it proves you can create loving characters. Just create another one.

THE EIGHTH QUESTION: HOW WILL MY MAIN CHARACTER ARC OVER THE MYSTERY DRAMA OR STORYLINE?

What fears or human frailty will the sleuth need to overcome in solving the crime? This is what drives a character arc. What will the main character ultimately learn? Does he have a fear of heights? Is she normally timid and now has to be courageous? What inner fears will be challenged when going about solving the crime and/or mystery?

What fears or human frailty will the sleuth need to overcome in solving the crime? This is what drives a character arc. What will the main character ultimately learn? Does he have a fear of heights? Is she normally timid and now has to be courageous? What inner fears will be challenged when going about solving the crime and/or mystery?

Where and how can you fit the revelation of these traits into the character backstory?

Is the protagonist isolated or alone in their struggle? If they lack support or are actively opposed by others, how can you show them overcoming this lack of support and calling on their inner resources?

NINTH QUESTION – WHAT ARE THE STAKES?

What will the main character need to risk achieving his/her goal? Has the detective been told he will be fired if he doesn't drop the case? Has the neighbor of a man who is gaslighting his wife been threatened with an expensive lawsuit? What is at stake and what change will be needed to get through the setbacks in the storyline? How will this change in character change the life of a main character? How can you show that final change in character in the ending of the book?

Knowing who the antagonist is, and knowing all of the suspects and their motivations will make it easier to come up with a customized main character flaw that will fit perfectly into the storyline.

Again, it's easier to create a character after you already know what he/she will be required to do physically, what skills they will need, and what human flaw can make this challenging. It's easier than forming a main character that you like and then trying to fit him or her into a storyline that already has a life of its own.

Again, it's easier to create a character after you already know what he/she will be required to do physically, what skills they will need, and what human flaw can make this challenging. It's easier than forming a main character that you like and then trying to fit him or her into a storyline that already has a life of its own.

It would be hard to fit a character like the father on Married with Children into a James Bond film and vice versa. Think of the skeletal plotline as an obstacle course. Once you know what physical stamina, hurdles, level of intelligence, investigative experience, and technical skills a main character will need to run the ball all the way down the field, it is easy to sketch up a character based on that obstacle course. You can easily add any quirky or funny bits to their personality later on.

Another consideration is how the hero's success or failure will affect others around him? Are innocent lives at risk? Is the fate of a community, a nation, or even the world hanging in the balance until the hero saves the day? The wider the impact, the higher the stakes.

Are his or her loved ones in danger? If the protagonist's family, friends, or romantic partner are threatened, the stakes become deeply personal and emotional. This raises the stakes too.

Is there a moral dimension to the conflict that raise the stakes? Does the protagonist's decision have far-reaching ethical implications? Is he/she fighting for justice, truth, or a greater good? Moral dilemmas add weight and complexity to the stakes.

Is there a moral dimension to the conflict that raise the stakes? Does the protagonist's decision have far-reaching ethical implications? Is he/she fighting for justice, truth, or a greater good? Moral dilemmas add weight and complexity to the stakes.

Looking down at your brainstorming outline, ask yourself: How can I add a little pressure into this plotline? What happens if he doesn’t solve the case? Who will be let down if he fails? What effect will failure to solve the mystery have on his world or our world?

As the suspects respond to questioning, will one or more of them throw in an outright lie or a lie of omission -- that only the reader will know -- that will send the main character down the wrong path? This will cause the reader to worry about the main character. What clue will ultimately uncover this red herring or subterfuge?

IS TIME PRESSING DOWN, ADDING TENSION AND HEIGHTENING THE STAKES?

Is there a ticking clock in your storyline? Is there a deadline to solve the crime? Is there a rapidly-approaching event that can significantly heighten the stakes? The faster the clock ticks, the more intense the pressure, the higher the stakes. This added time pressure can turn a mystery into a thriller.

Is there a ticking clock in your storyline? Is there a deadline to solve the crime? Is there a rapidly-approaching event that can significantly heighten the stakes? The faster the clock ticks, the more intense the pressure, the higher the stakes. This added time pressure can turn a mystery into a thriller.

If you haven't figured a time element into the storyline yet, think about how you can use time in a way to add tension into the plotline.

TENTH QUESTION: UNEXPECTED TWISTS AND TURNS:

Most readers like a surprise twist or unexpected turn. What twist or turn can you add into the mix to heighten the stakes and keep readers guessing?

Is there a sense of uncertainty or ambiguity about the clues? If the outcome is uncertain and the protagonist is forced to make difficult choices with limited information, this too can add tension and heighten the stakes.

If you can't think of an unexpected twist and turn at this point, it's okay. My experience has been that whatever doesn't come in the brainwashing session will come in the next layer of writing which is outlining the scenes.

CONCLUSION:

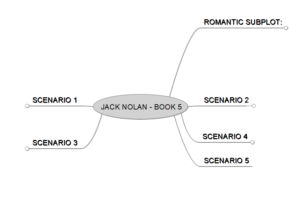

Before I begin a new novel, I brainstorm a minimum of four potential storylines. I go through these questions in this order and come up with an actual storyline. Then I pick the best one, the one I know calls to me to be written. So I know this brainstorming strategy works.

Before I begin a new novel, I brainstorm a minimum of four potential storylines. I go through these questions in this order and come up with an actual storyline. Then I pick the best one, the one I know calls to me to be written. So I know this brainstorming strategy works.

It took me one full year to come up with my first storyline and I thought about it everyday. But I didn't know where to start or how to proceed. My goal in this two part blog and video series is to help the newbies get over that first initial hump of getting a workable storyline. I hope this will work for some of you.

Below is the video that was done on this material:

When Brainstorming a Novel Storyline, what questions do you need to ask and answer? After having written 14 novels, I believe this technique that I'm about to tell you about will help anyone brainstorm a working plotline.

When Brainstorming a Novel Storyline, what questions do you need to ask and answer? After having written 14 novels, I believe this technique that I'm about to tell you about will help anyone brainstorm a working plotline. What will the mystery or crime in the novel be? Will it be a psychological thriller and mind control is the crime? Will it be a murder mystery? If so, what is the cause of death? If it's a science fiction plotline, what mystery will hook the reader and thread through the entire story only to be revealed at the end?

What will the mystery or crime in the novel be? Will it be a psychological thriller and mind control is the crime? Will it be a murder mystery? If so, what is the cause of death? If it's a science fiction plotline, what mystery will hook the reader and thread through the entire story only to be revealed at the end? The type of crime or mystery will dictate the investigation methods and details. It will also dictate what clues will be needed in order to slowly reveal the mystery throughout the four-part plot structure.

The type of crime or mystery will dictate the investigation methods and details. It will also dictate what clues will be needed in order to slowly reveal the mystery throughout the four-part plot structure. Is he/she a private detective, an amateur sleuth, a police officer, or maybe just a weekend visitor who is inadvertently led into solving a mystery?

Is he/she a private detective, an amateur sleuth, a police officer, or maybe just a weekend visitor who is inadvertently led into solving a mystery? Determine the identity, background, and significance of the victim. This decision can affect the motive, the suspects, and the overall narrative story arc. The victim's characteristics can also influence how the crime impacts other characters or the community at large. Before figuring out who the suspects are, you need to know who the victim is and why they were murdered or wronged in some way. If it's not a crime story but just a mystery or thriller, you will still need a victim. They may not die in the story, but there will be at least an injustice done to them. What is that injustice and who is the victim of it?

Determine the identity, background, and significance of the victim. This decision can affect the motive, the suspects, and the overall narrative story arc. The victim's characteristics can also influence how the crime impacts other characters or the community at large. Before figuring out who the suspects are, you need to know who the victim is and why they were murdered or wronged in some way. If it's not a crime story but just a mystery or thriller, you will still need a victim. They may not die in the story, but there will be at least an injustice done to them. What is that injustice and who is the victim of it? The victim's background, their relationships, and their secrets are all vital. Were they likeable? Did they have known enemies? A compelling victim, even if flawed, gives the reader someone to care about and root for. Even if the victim hasn't been killed or murdered, who is being bullied or targeted as the victim and why?

The victim's background, their relationships, and their secrets are all vital. Were they likeable? Did they have known enemies? A compelling victim, even if flawed, gives the reader someone to care about and root for. Even if the victim hasn't been killed or murdered, who is being bullied or targeted as the victim and why? Where will the story play out? Most stories will have multiple stages, but where will most of the action take place? Will it be a haunted estate house? A corrupt business office? Will it be on the streets in a cityscape? How does the setting influence the mood and the unfolding of the mystery? For example: If it's a gothic novel, you will want a large estate house or a monastery, a place that has secret rooms, tunnels, or has a long history with lots of secrets. If it's a urban thriller, you will need several stages in a city scape. If it's a psychological thriller, it may need at least a mental institution. Think of yourself as a location scout for a movie: What interesting places can most of the drama take place?

Where will the story play out? Most stories will have multiple stages, but where will most of the action take place? Will it be a haunted estate house? A corrupt business office? Will it be on the streets in a cityscape? How does the setting influence the mood and the unfolding of the mystery? For example: If it's a gothic novel, you will want a large estate house or a monastery, a place that has secret rooms, tunnels, or has a long history with lots of secrets. If it's a urban thriller, you will need several stages in a city scape. If it's a psychological thriller, it may need at least a mental institution. Think of yourself as a location scout for a movie: What interesting places can most of the drama take place? Choose a location that not only serves as a backdrop or a stage for the events to take place but which can become its own character. What secrets does the location harbor? Who lived in the historic mansion in another era? Will you need a remote island somewhere to have a closed-door mystery? In a city scape, the backdrop may be about about the certain era, or just a gritty story, or a surreal story. In a mystery drama, what happened in the main family that started all the secrecy? What sin has been passed down through the generations? What corporate setting do you need to show back-door deals or money laundering? What setting can you choose that will enhance the story?

Choose a location that not only serves as a backdrop or a stage for the events to take place but which can become its own character. What secrets does the location harbor? Who lived in the historic mansion in another era? Will you need a remote island somewhere to have a closed-door mystery? In a city scape, the backdrop may be about about the certain era, or just a gritty story, or a surreal story. In a mystery drama, what happened in the main family that started all the secrecy? What sin has been passed down through the generations? What corporate setting do you need to show back-door deals or money laundering? What setting can you choose that will enhance the story?

Will the story be set in a specific time period? Will it be a general contemporary book that won't reference any specific time period at all? Or will it be specifically cast in an era or time period that will require research?

Will the story be set in a specific time period? Will it be a general contemporary book that won't reference any specific time period at all? Or will it be specifically cast in an era or time period that will require research?

If you are stumped for a main story, or if you are stumped for what happens now, or even if you have written yourself into a bit of a corner, this instructional will help, along with your own creativity and thinking, to bring about new possibilities.

If you are stumped for a main story, or if you are stumped for what happens now, or even if you have written yourself into a bit of a corner, this instructional will help, along with your own creativity and thinking, to bring about new possibilities.

Once you have a perpetrator and the cast of necessary characters, then it’s time to answer the following questions:

Once you have a perpetrator and the cast of necessary characters, then it’s time to answer the following questions:

Before you exert too much energy fleshing out any character or story details, be sure to check to make sure you can design a three-prong storyline out of this budding storyline. One prong will be a red herring storyline, someone who may look guilty, but is exonerated in the middle or end of the story. The second prong is a second suspect or a wrong suspect who will look guilty for a large segment of the storyline. And the final prong will be for the real culprit. In order to have a story that works, you will need a believable crime that can meld these three prongs into one suspenseful story.

Before you exert too much energy fleshing out any character or story details, be sure to check to make sure you can design a three-prong storyline out of this budding storyline. One prong will be a red herring storyline, someone who may look guilty, but is exonerated in the middle or end of the story. The second prong is a second suspect or a wrong suspect who will look guilty for a large segment of the storyline. And the final prong will be for the real culprit. In order to have a story that works, you will need a believable crime that can meld these three prongs into one suspenseful story. As you use this worksheet and these techniques, a crime skeleton will emerge. Some attempts at this will go flat in the early stages for any number of reasons. But some storylines will begin to almost shape themselves.

As you use this worksheet and these techniques, a crime skeleton will emerge. Some attempts at this will go flat in the early stages for any number of reasons. But some storylines will begin to almost shape themselves. Writing a novel is a huge undertaking. There are many things that go into the writing of a fiction story. The best tip I can pass on is this: Break everything down into little bite-sized pieces. By doing this, you can reduce a huge project down to do-able portions that can be done whether you have 2 hours a week to write or two full days! It only requires a little planning and organization.

Writing a novel is a huge undertaking. There are many things that go into the writing of a fiction story. The best tip I can pass on is this: Break everything down into little bite-sized pieces. By doing this, you can reduce a huge project down to do-able portions that can be done whether you have 2 hours a week to write or two full days! It only requires a little planning and organization. It’s important to keep reading as your own journey as a writer continues. Each author has a different style and uses different storytelling techniques. The stories don’t even have to be great. You can learn from the good, the bad and the bland. Just analyzing what made a book bland is a great lesson in itself. Did the story need more action? Did the story get stuck somewhere?

It’s important to keep reading as your own journey as a writer continues. Each author has a different style and uses different storytelling techniques. The stories don’t even have to be great. You can learn from the good, the bad and the bland. Just analyzing what made a book bland is a great lesson in itself. Did the story need more action? Did the story get stuck somewhere?  or other books you read. Reading other authors is crucial no matter where you are on the writing spectrum. However, when you’re new, you can learn a lot from watching mystery or crime noir movies. I like movies from the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. The movies in these decades didn’t have CGI and the directors had to use the stage to tell the story. They used wider shots and props to assist the storytelling. By watching these older movies, you can learn a lot regarding writing.

or other books you read. Reading other authors is crucial no matter where you are on the writing spectrum. However, when you’re new, you can learn a lot from watching mystery or crime noir movies. I like movies from the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. The movies in these decades didn’t have CGI and the directors had to use the stage to tell the story. They used wider shots and props to assist the storytelling. By watching these older movies, you can learn a lot regarding writing.  It’s a good idea to read the synopsis before you view the movie. Knowing at least a basic outline of the story will allow you to absorb more as an author. If you go into the movie blindly, you will be “experiencing the movie” as a viewer only. By knowing ahead of time what story will be unfolding, it will allow you to watch specifically for certain scenes to unfold. You can watch what tools are used to move the story along.

It’s a good idea to read the synopsis before you view the movie. Knowing at least a basic outline of the story will allow you to absorb more as an author. If you go into the movie blindly, you will be “experiencing the movie” as a viewer only. By knowing ahead of time what story will be unfolding, it will allow you to watch specifically for certain scenes to unfold. You can watch what tools are used to move the story along.

If you are looking for a suggestion, I would suggest Rebecca for the first movie. This movie was directed by Alfred Hitchcock and it has a lot of gothic atmosphere. There is also a psychological plotline in this story so it is a goldmine for learning storytelling tools.

If you are looking for a suggestion, I would suggest Rebecca for the first movie. This movie was directed by Alfred Hitchcock and it has a lot of gothic atmosphere. There is also a psychological plotline in this story so it is a goldmine for learning storytelling tools.  When I first decided to write a novel, it took me one full year (I’m not kidding!) to even come up with a crime. Today, using these methods I’m about to reveal, it only takes me two to three days to think up three or four mystery scenarios.

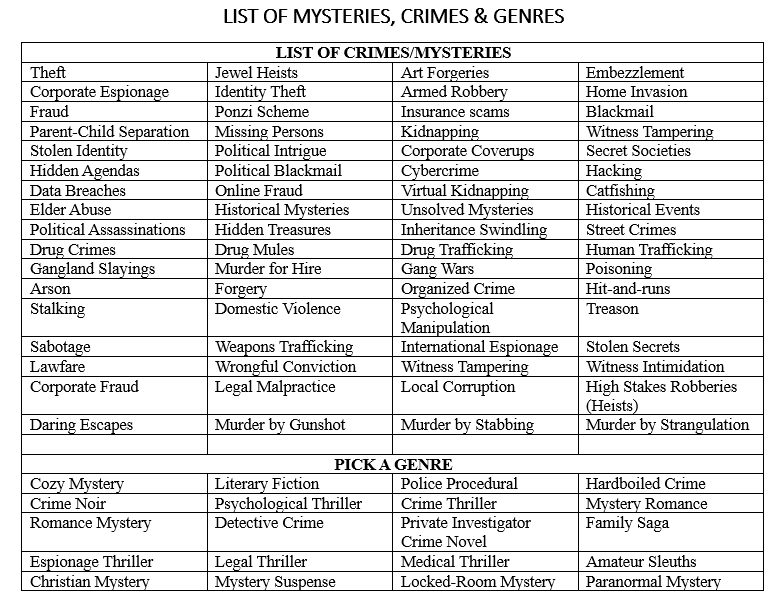

When I first decided to write a novel, it took me one full year (I’m not kidding!) to even come up with a crime. Today, using these methods I’m about to reveal, it only takes me two to three days to think up three or four mystery scenarios. Let’s talk about how to use this work sheet. Choose a crime or mystery from the list below and make up a potential perpetrator. Don’t waste time on what he or she looks like. Then start asking the following questions:

Let’s talk about how to use this work sheet. Choose a crime or mystery from the list below and make up a potential perpetrator. Don’t waste time on what he or she looks like. Then start asking the following questions: Once you have a perpetrator and the cast of necessary characters, then it’s time to answer the following questions:

Once you have a perpetrator and the cast of necessary characters, then it’s time to answer the following questions: